Ever since studying theology at University and thereafter becoming engaged in experiential human development, I’ve been drawn to the mystery of who humans are and how they operate.

The crux of it is that self-consciousness defines us as a species. Not exclusively as some scientists now believe but certainly predominately.

The ability to witness our own thoughts and actions is a source of learning and sometimes transcendence. Getting beyond the programming.

In front of me is an article marshalling the evidence that unconscious bias training does not work. The UK government’s so called Nudge Unit was commissioned in 2020 to review the evidence and concluded:

“There is currently no evidence that this training changes behaviour in the long term or improves workplace equality in terms of representation of women, ethnic minorities or other minority groups” and sometimes had unintended “negative consequences”.

There is understandable concern amongst equity activists that snubbing out any value, however small, is a step backwards in the generations long struggle to make progress. They sense there is a certain convenience in this conclusion. Allowing the status quo to avoid having to witness their own thoughts and actions and hopefully through self-reflection transcend negative habitual behaviour.

The aim to enlighten is the right one. The belief that a training alone can achieve such as shift is a naïve one.

But equally, the need for this education is essential if the aims of diversity and inclusion are to be realised. Human history is often a story of struggling to be on the winning side. The narrative around successful tribes is that they appear to win at the expense of others. Power with compassion remain oil and water in this respect. I win therefore you lose. In fact, you must lose to validate my victory.

Resetting A Poverty Mindset

No surprise then this is deeply engrained in our collective psyche. The flip side of this belief is just as potent. I lose if you win. And based on that, I must stop you. Heather McGhee provides a vivid example of how such collective fears reduce our humanity in her new book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper.

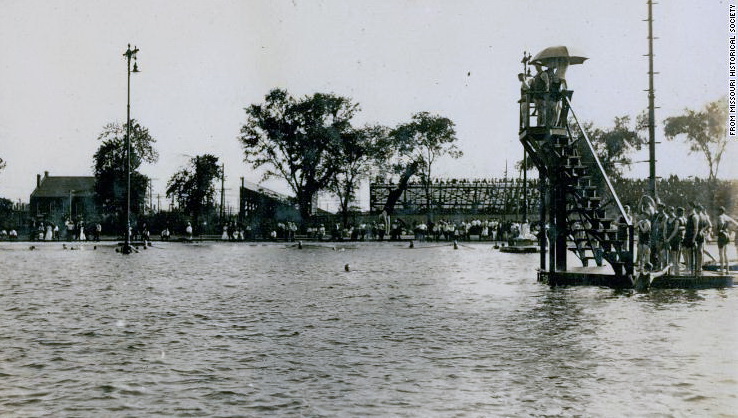

Civic pride in early twentieth century America led to the creation of wonderful open-air pools. They were huge. Able to cater to many thousands. But only for whites. Once civil rights challenged that restriction and won access, many cities responded by selling these public assets off. Or in the case of the Fairground Park pool in St. Louis which is pictured below (courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society), they closed it down.

McGhee calls this ‘drained-pool politics’. When black or brown people gain something, white people lose. Even though removing these facilities also damages quality of life for white families too. But this point is missed when fear reduces people to bloody minded meanness. The same poison drives gender inequalities too.

Where Unconscious Bias Fits In

From the perspective of understanding what is needed to neutralise this unconscious belief, appealing to logic falls short. It simply skims over the top of this deluded mindset in spite of the evidence. As McGhee says in a CNN interview,

research shows that diversity allows groups to think better about critical problems. It is the friction of coming from different backgrounds and looking at issues from different vantage points that creates a productive energy.

This is a popular ROI in EDI strategy. (Equality, Diversity & Inclusion). When the moral case is not sufficient bait then surely souped-up team performance in high competition, innovation led economies must win the argument for executives who are being asked to sign off on Diversity and Inclusion?

Trouble is unconscious bias training can become the new and shiny thing that promises much for seemingly little investment. We can readily show how it links to popular recommended changes in the EDI roadmap such as blind recruitment techniques.

Here is a story told by inclusion strategist Vernā Myers on this very topic.

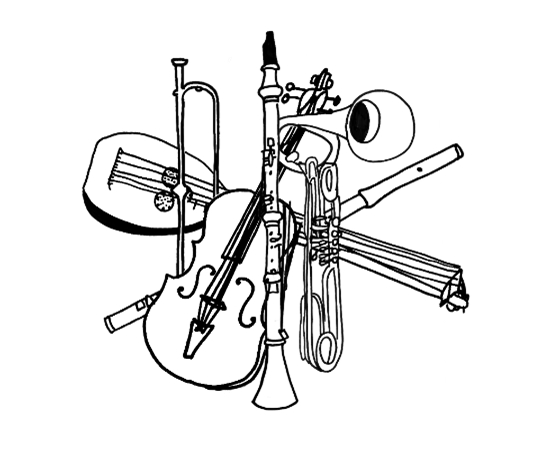

US orchestras immediately started adding more female members once auditions effectively masked a candidate’s gender using a combination of screens, a strict policy of no talking and carpets to disguise the acoustic identity of candidates arriving on stage. Those in charge had recognised they were being more influenced by what they saw than heard. Deeply ironic given the business of an orchestra!

This kind of example shows the challenge trying to transcend these mental short cuts and filters we constantly use to make everyday decisions. As an issue it’s tough and deep. Therefore it requires a far broader approach to the topic of how humans experience their reality, the mechanics involved and the implications for how they interact and engage others.

Therefore, organisations need to carefully think through how they take on this commitment which is probably the most extensive investment in personal development they will have encountered to date.

The good news is that some educational material is probably already within the collective knowledge of organisations. For instance, if you have invested in EQ (Emotional Intelligence), you will have relevant foundational material on how the mind works.

Those with an existing culture of lifelong learning should also have stronger foundations to build on. Learning cultures recognise that we learn better when we can personalise. Beyond the general point of needing to cater to different learning styles, people will have different starting points on unconscious bias and its associated topics. Some like to think about the way human minds work and might actively practice self-awareness. Others might need the motivation to start looking.

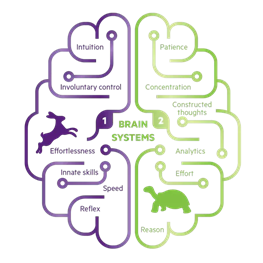

And however self-aware we might personally judge ourselves to be, the EDI educational aim needs to recognise we are all implicated in the negative impacts of unconscious bias. Why? Because we all share common brain structures and coping mechanisms. Unconscious bias is not just a bad habit of those who cause inequalities. We all do it. Life would be an overwhelming experience if everything had to be consciously experienced and processed.

We use high octane, conscious attention only as needed. Otherwise, we run much of our lives on automatic; relying on habit, selective memories, acquired beliefs and inherited cultural DNA to inform our responses.

In our busy worlds, the upside is that so called system one thinking is fast, energy efficient and helps us survive. But the same mental process that can also reduce the uniqueness of an individual to stereotyping. And sometimes those filters can be fatal.

This afternoon I watched a Panorama documentary that investigated why black people are twice as likely to die in police custody in the UK as whites. 27 deaths in the last 15 years. They are also three times more likely to have force used against them. Police body cams at one inquest showed how one such situation unfolded.

Kevin Clarke was experiencing a mental health episode. Lying incapacitated on the grounds of a school playing field. Police arrived. At no point did he move violently or suddenly. Yet the group of officers felt a collective need to restrain him with cuffs and leg restraints. One female officer is seen instinctively reaching for her taser as Kevin slowly attempts to sit up.

They are not seeing a victim of mental health in need of care, they are seeing a threat that needs subduing. The stereotype manifested as big, unknown and dangerous.

So powerful, it overrode any compassion or health related urgency from the group even when an ambulance crew arrived. All remained polite and professional throughout. Yet Kevin died as a result. I did not sense any of those officers consciously intended that outcome. But it happened.

Loss of life is the extreme consequence of a set of mental processes we all use daily. They also damage people’s dignity, life opportunities, and sense of belonging. These so-called micro aggressions are daily realities.

Understanding the mechanism does not mean we tolerate the damage it causes others. We all need to take positive steps to close the gap between what we imagine about others and what is real about them.

Single shot trainings on unconscious bias undoubtably fall short. But that does not invalidate the urgent need to educate and self-manage. It simply means we must take the challenge much more seriously and invest accordingly. As I started out by saying, humans self-reflect and learn how to modify their behaviour. It takes time, support, motivation and often courage. But it is possible.

If your EDI aims express the intent of eliminating racism within your organisation, then your response needs to recognise everyone is involved in becoming part of the solution by stopping being part of the problem.

For some this has been an urgency for ever. For others it takes some inner work to move from the comfort zone of seeing yourself as a neutral influence (not my fight, just getting on with my life) to tracing the threads and becoming involved. A compelling EDI plan helps everyone recognise the importance and means to contribute. This happens through ongoing education, safe spaces for self-discovery and practical input to change your experiences of others.

Ways To Improve

In summary, here are three suggestions to strengthen your EDI strategies.

- Reposition unconscious bias as one topic in a broader curriculum of action learning and personal commitment to become part of the solution.

- Individuals begin their EDI journeys differently based on their life experience. Each need narratives and support that make sense from the perspective they hold. Value everyone’s experience before expecting changed behaviour.

- Shared reality comes from shared experiences. Create ongoing opportunities to mix it up, tell stories, change mindsets and alter memories.

Thanks for reading.